The years preceding and following the moment you retire can dictate not only the quality of your golden years but also the likelihood you’ll have enough to last throughout retirement.

“As you approach retirement, each move—and misstep—carries a lot more weight,” says Chris Kawashima, CFP®, a senior research analyst at the Schwab Center for Financial Research. “Fortunately, with careful stewardship and a little flexibility, you can successfully adjust your retirement plan if you find yourself off course.”

Schwab recently asked more than 150 people nearing retirement with at least $1 million in savings about their approach to this pivotal transition.1 Taking their concerns into account, here are some key risks—and potential solutions—to be mindful of as you navigate the so-called dangerous decade.

Risk: Lifestyle creep

The final years of your full-time career often coincide with your peak income. But as your earnings grow, so can your expenses—and if you’re not saving at the same rate, it could be difficult to sustain your lifestyle into retirement. Many savers assume they’ll need less income in retirement because they’ll no longer be saving for retirement. However, some expenses, such as health care and travel, could actually increase.

“When I retire, I expect to be active and to travel more than I do now,” says Jill A., who feels somewhat confident in her financial plan but remains unsure about when to cease working. “I’ve been aggressively saving and investing in the hope that I will not have to downsize my current lifestyle.”

When estimating retirement expenses, most people should plan to spend as much as they do preretirement. For example, a couple that earns $300,000 annually will need roughly 15 times that amount, or $4.5 million, to sustain their standard of living over a 30-year retirement. “They won’t need all that money on Day 1, but they’ll need it eventually,” says Susan Hirshman, director of wealth management at Schwab Wealth Advisory, Inc. “And if they’re not increasing their savings in proportion to their rising income, they could be forced to make some difficult decisions down the road.”

Solution: Ramp up savings

Assuming you’re already maxing out your 401(k), IRA, or both, consider putting additional savings in:

- Taxable investments: Unlike tax-deferred savings, which are taxed as ordinary income, withdrawals of long-term gains from your taxable accounts are assessed at 0%, 15%, or 20%, depending on your income (plus a 3.8% surtax for higher earners). What’s more, you’re not required to take minimum withdrawals beginning at age 73 as you are with tax-deferred accounts, giving you greater flexibility over your income and your tax bracket.

- A qualified employer plan: Some workplace retirement plans allow after-tax contributions above and beyond typical annual contribution limits, up to a combined maximum (employee plus employer contributions) of $66,000 in 2023 ($73,500, including catch-up contributions, for those age 50 or older).

Risk: Too conservative, too soon

As they near retirement, many investors believe they should start shifting to a more conservative portfolio allocation that favors capital preservation over growth. However, paring stocks too soon could undermine your portfolio’s longevity potential.

“There’s a misguided notion that you should cut way back on stocks by the time you retire, but that’s not always the wisest approach,” Chris says. “If you want your portfolio to last through or beyond your lifetime, the potential for continued growth is an important factor.”

Solution: Consider going moderate

Today’s retirees may want to keep more than half of their investable assets in equities in their first decade of retirement. “The rationale behind such a stock-heavy portfolio has to do with life expectancy,” Chris says. “Those who stop working at age 65 may need to stretch their savings for 25 years or more, and stocks can help offset the risk of outliving your savings.”

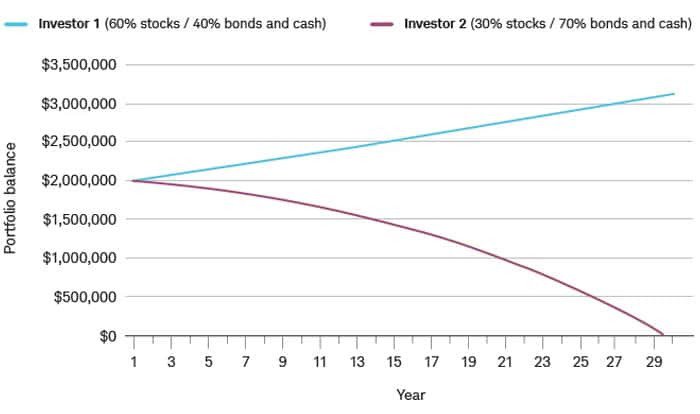

For example, a $2 million portfolio comprising 60% stocks and 40% bonds and cash would be worth nearly $3.1 million after 30 years, whereas a portfolio comprising 30% stocks and 70% bonds and cash would be depleted between years 29 and 30—assuming a 4% withdrawal rate in the first year of retirement and adjustments for inflation thereafter. A financial planner can help assess your specific needs and run different scenarios to determine how much and what type of stock exposure makes sense for your individual circumstances.

Your mix matters

A $2 million portfolio with 60% stocks and 40% bonds and cash would significantly outlast one with 30% stocks and 70% bonds and cash, all else being equal.

This example is hypothetical and for illustrative purposes only. Both investors took a 4% portfolio withdrawal in the first year of retirement, increased 2% annually thereafter to account for inflation. The 60/40 portfolio’s performance assumes a 6% average annual return, and the 30/70 portfolio’s performance assumes a 3% average annual return. Returns do not reflect expenses, fees, or taxes.

Risk: Insufficient liquidity

“Between the market downturn and severe inflation, it makes me think I may never be able to retire,” says Stephen T., an investor who would like to stop working within six to 10 years. “I’m feeling like I need to take bigger risks to have a better chance at retiring.”

In fact, a market downturn such as last year’s can be particularly threatening in the first few years of retirement. If you tap your portfolio as it’s losing value, you’ll need to sell a greater proportion of investments to meet your income needs.

“Not only does that drain your savings more quickly,” Susan says, “but it also leaves you with fewer assets to potentially generate returns when the market eventually recovers.” If a decline occurs in your later years, on the other hand, your portfolio presumably would be smaller and, therefore, so would the hit.

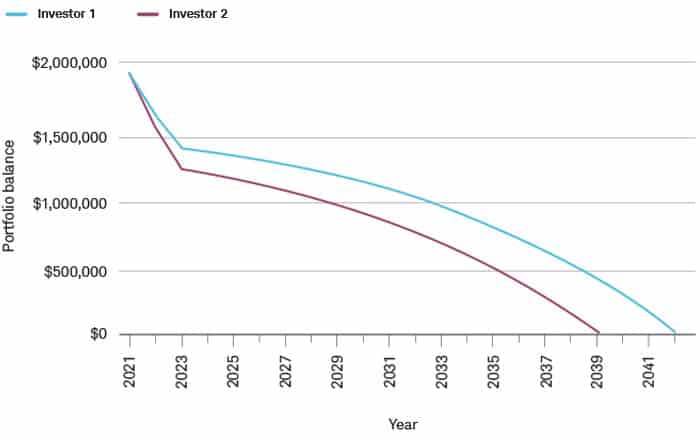

Rough start

Making a large withdrawal from your savings during a downturn, especially if the decline occurs in the first few years of retirement, can seriously erode your portfolio’s longevity.

Investor 1 didn’t have short-term reserves and was forced to withdraw a year’s worth of income from their portfolio in 2022, a year in which their portfolio was already down 16%. Assuming a similar market decline in 2023, their portfolio would be depleted by 2039.

Investor 2 had enough short-term reserves to avoid taking portfolio withdrawals in 2022 and 2023. Because of this, their portfolio would last three years longer than Investor 1’s, assuming identical future returns and withdrawal amounts.

This chart is hypothetical and for illustrative purposes only. Both hypothetical investors had a starting balance of $2 million; a portfolio mix of 60% stocks and 40% bonds and cash; and experienced a –16% return in 2022, a –15% return for 2023, and a 6% return for every year thereafter. Investor 1 took a $100,000 withdrawal in Year 1 and increased subsequent withdrawals 2% annually to account for inflation. Investor 2 took no withdrawals in the first two years of retirement, a $104,040 withdrawal in Year 3, and increased subsequent withdrawals 2% annually to account for inflation. These scenarios do not reflect expenses, fees, or taxes.

Solution: Shore up your reserves

It’s important to assess your ability to take on risk when preparing for retirement. Having adequate short-term reserves can help you avoid selling assets in a down market. “Most retirees should have at least a year’s worth of expenses in a highly liquid account, such as an interest-bearing checking or savings account,” Susan says, “plus an additional two to four years’ worth of income set aside in stable, relatively liquid investments, such as short-term bonds or bond funds, which are fairly easy to draw upon and typically generate more income than cash and its equivalents.”

Risk: Failing to plan for long-term care

“My main concern is health care,” says Kenneth S., despite otherwise feeling confident in the amount he’s put away toward retirement. “With the rising costs and uncertainty surrounding this subject, the future is murky at best.”

Indeed, health care spending is top of mind for many soon-to-be retirees—and with good reason. A 2020 report from the Employee Benefit Research Institute estimates a 65-year-old couple could need as much as $325,000 in savings to cover their health care expenses in retirement—and that doesn’t include an often-overlooked expense that nearly 70% of retirees will face at some point: long-term care.

“Medicare can help cover most health care costs in retirement, but unfortunately that’s not the case when it comes to long-term care,” Chris says. If you end up needing help with daily living activities, such as bathing and eating, you’ll be on the hook for covering such services yourself—the cost of which can be exorbitant.

Sticker shock

The annual cost of long-term care is formidable—and rising.

| Type of care | Average annual cost | Year-over-year increase |

|---|---|---|

| Assisted living facility | $54,000 | 4.65% |

| Home health aide | $61,776 | 12.50% |

| Nursing home, semiprivate room | $94,900 | 1.96% |

| Nursing home, private room | $108,405 | 2.41% |

Source: Genworth, Cost of Care Survey, 2021.

Solution: Consider long-term care insurance—ideally before age 65

The best time to buy a long-term care policy generally is between the ages of 50 and 65, after which premiums can skyrocket. For example, the average annual premiums for a healthy 65-year-old man and woman are $1,700 and $2,700, respectively. Premiums for a policy purchased at age 75 would be nearly double those figures, assuming coverage is even available (nearly half of all applicants in their 70s are rejected).

In our survey, respondents expressed high premiums as the primary reason for eschewing long-term care insurance. While paying between $1,700 and $2,700 annually may seem costly, it pales in comparison to the average annual cost of a private room in a nursing home, which will run you some $108,000. “It’s true that you may never end up tapping such a policy,” Chris says, “but the downside of not having coverage can be considerable. You should take into account your family history, overall health, and financial situation when determining whether long-term care insurance is right for you.”

Those who don’t qualify for long-term care insurance due to a preexisting condition might consider maxing out contributions to a health savings account (HSA), if available, to help prepare for the potential financial hit of long-term care. Generally, contributions to an HSA are made with pretax dollars, money in the account can grow tax-free when invested, and withdrawals also are tax-free if used for qualified medical expenses. In 2023, savers ages 55 and older can contribute $4,850 as an individual or $8,750 as a family, which includes a $1,000 catch-up contribution.

“Even if you do qualify for a long-term care policy, maxing out your HSA also makes sense since you can use HSA funds to pay for long-term care insurance premiums,” Chris says.

Don’t go it alone

As with any period of uncertainty, navigating the dangerous decade successfully comes down to anticipating the risks and, to the extent possible, future-proofing your plan.

“The economy and market are very volatile, so planning for retirement is always a work in progress,” says Robert F., a Schwab client who reviews his investments regularly with a financial consultant. A financial consultant can help you determine which obstacles you may face as you approach and enter retirement, and what steps you can take now to mitigate them. “I am optimistic over time and make changes when necessary,” he says.

“Forewarned is forearmed,” Susan says. “The earlier you create and pressure-test your retirement plan, the more successful it’s likely to be.”